Encompassing the Charm of Alsace

A Brief History of Alsace Wines

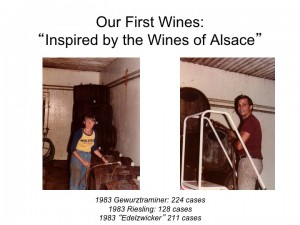

Part of what makes Claiborne and Churchill so unique and special is our production of Alsatian white wines. These wines are virtually unheard of among novice wine enthusiasts. Alsatian wines originate from the region of Alsace in France, producing delicious, high quality wines, dryer in contrast to their neighbors in Germany. The German-influenced wines are often sweeter, but produced from the same grape varietals.

Wines such as Rieslings and Gewürztraminers are today generally misconceived as being “too sweet” in the United States. This is mostly due to a sweeter style with higher residual sugar evident in these wines in the 90’s. Many producers who work organically didn’t want to pick grapes before they reached total ripeness and didn’t want to add store-bought yeast to complete fermentation that indigenous yeast couldn’t. This resulted in the wines retaining more sugar post fermentation. Due to the popularity with consumers and some wine critics preferring the sweeter wines and rewarding them with high scores, winemakers were discouraged from changing their methods until more recently.

Vintners began to adjust their viticultural methods to define ripeness with lower sugar content in the grapes. Winemakers have worked to achieve beautiful acidity and vibrancy rather than letting the sugars take over and being stuck with a syrupy product.

Embracing Tradition

Our take on Alsatian wines pays homage to how they were traditionally produced and enjoyed. Because of our proximity to the ocean, cool coastal breezes and morning fog create a growing environment similar to that of the Alsace region, yielding in Rieslings and Gewürztraminers with evident floral, spicy, and an array of fruit notes balanced with excellent acidity. We celebrate a harmonious balance of fruit and oak, structure and texture.

For more information, click here for a fabulous article that goes more into depth on the history of the Alsace region wines.